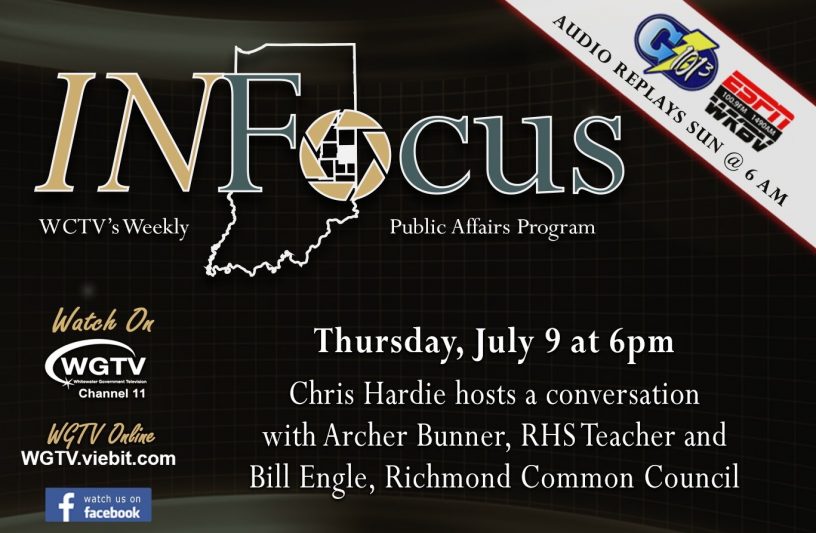

In July I’m continuing to guest host a few episodes of the public affairs program IN Focus on WCTV, talking with my guests about racism and what it means for people in our community — especially white people — to be listening, learning and taking meaningful anti-racist action so that everyone who lives here can know justice.

In today’s show, I talk with Archer Bunner, a teacher at Richmond High School and a leader with the Alternatives to Violence Project, about wrestling with bias and racism in a classroom setting, and how thinking about different models of conflict resolution could complement calls to change how policing works. In the second segment I talk with Bill Engle, member of Richmond’s Common Council and a former local reporter, about the role that local government might play in addressing racism, and what it looks like for Richmond as a city to really work on these issues together.

With both Archer and Bill I appreciate that they were willing to talk openly with me about the challenges of confronting and working on racism in our lives and professions. They were candid about the concerns they’ve faced, and in that I think they modeled that we don’t have to have all the answers to make progress. I learned from these conversations and I hope you will too.

I welcome your feedback. You can watch the video below, on WCTV’s YouTube channel, on Facebook or as the episode is replayed on WGTV Channel 11. The audio of the show is also available via the Richmond Matters podcast feed, which you can find in your favorite podcast listening app.

Disclosure: as I note in the episode itself, I was a contributor to Bill Engle’s 2019 election campaign for Common Council.

Transcript

The below transcript was generated with the use of automation and may contain errors or omissions.

Chris Hardie: Hi, and welcome to this week’s IN Focus on Whitewater Community Television’s WCTV Channel 11. I’m Chris Hardie, and I’m sitting in for Eric Marsh as your host for a few episodes here in July. As with last week, in these conversations, we are continuing to look at what it means for our community to work on and really make progress on the serious, and historic challenges of racism and racial discrimination. In particular, we’re exploring what it means for white people here to join in and attempt to understand our role in systems of racism, what privileges and biases contribute to that, and what actions we can take to be a part of the solution.

As white people, I think we need to show that we are listening, that we are understanding, and that we are willing to do some hard work on ourselves in the name of justice for all. My two guests this hour will help us have a part of those conversations. In a bit, I’ll be talking with Bill Engle, a member of Richmond’s City Council, and a former local reporter. First, I’m talking with Archer Bunner, a teacher at Richmond High School, and a conflict resolution workshop facilitator. Archer, thanks so much for joining me today.

Archer Bunner: Thank you.

Chris: If you could, just tell us a little bit about your background and the kinds of work that you do.

Archer: Great. Yeah, my name is Archer Bunner. I’m a teacher at Richmond High School. I teach mostly in the Math Department under the special education wing. I work with students who have identified learning disabilities of all types. I also teach a conflict resolution class. That class comes from a nonprofit that I work with called The Alternatives to Violence Project. It’s a national and international nonprofit that runs conflict resolution workshops in schools, communities and prisons. A lot of what I spend my time doing is working with them and working at the school.

Chris: Awesome. My understanding is you’ve taught that workshop in lots of different settings, lots of different contexts, group sizes and everything else. Is it material that you feel just really comfortable with at this point? Or is it an area where you are still learning? How does one master the area of conflict resolution?

Archer: Well, facilitating the workshops is certainly an area that I feel very comfortable with, but practicing conflict resolution, your life is a never-ending process. Practicing all of the different skills that you learned, particularly how to be defensive and react in a way that de-escalates a situation rather than escalates a situation, and how to attempt to address conflict even when you feel some fear. Those are definitely things that I still struggle with, which is one of the reasons why I stay working with the program. It’s not a program that’s about teaching other people to deal with things. It’s a personal growth thing. Everybody who comes is working on themselves together, to try and keep getting better at addressing those conflicts that are making our lives more difficult.

Chris: Sounds really powerful. We’ll, in just a little bit here, get to the connection between that exploration and personal growth with conflict resolution and racism, and systemic racism. We’ve been talking the last couple episodes here about the challenges of racism and white privilege, and especially what white people can do to make sure that we are listening, that we’re understanding, and that we’re taking meaningful action. I think about the classroom setting in the school system as a place where the young people in our community are undoubtedly having opportunities to see racism, to maybe understand it, maybe to confront it. I wonder if you can share a little bit about what you’ve seen, just as a teacher in that setting, even before some of the recent renewal of attention to racism in our community and around the country has happened. What have you noticed?

Archer: I’ve been teaching for six years at the high school, and then I had a year of student teaching where I was actually Hibberd, in the LOGOS program and at the high school. Throughout my entire career as a teacher, race and racism is definitely on the minds of the young people that I work with, in ways that ebbs and flows. It seems that there will be sometimes connected to a national movement or sometimes connected to some of the shootings that have happened by police. There’ll be a big burst of energy where students are really talking about it, arguing with each other, having conversations, talking with me about it.

Other times, just for seemingly no reason, it just seems to be a big topic that will just run throughout the school, and students will be really focused on thinking and talking about it. It’s definitely something that students, in particular, notice and want to talk about, want to explore. I would say, some of my personal experiences in the classroom that I’ve struggled with around racism are when students do call me racist, which definitely has happened. Especially when I was a younger teacher, and especially before I started really working on myself, I was very defensive about this. I didn’t think of myself as a racist. No, I didn’t think what I was doing was really separate, and that I was trying to tell them what they were doing was inappropriate, yelling or throwing something in class, or just being a distraction, right?

Things that I saw, as a teacher, as typical things that you should try to tell students not to be doing in the classroom. Over time, well, I went through some trainings, some anti-oppression trainings, and I realized it’s less about my response, my defensiveness, or me thinking I’m not a racist, and more about whatever it was that I did that made that student say that, that’s important for me to try to understand and address, regardless of my own personal feelings about myself because whatever it was that I did is making that student feel unsafe or uncomfortable in the classroom. It needs to be worked on. That’s definitely something that I have experienced and try to continue to think about in myself. Yeah.

Chris: Yeah. I mean, what does that look in an ideal situation, in that classroom setting where that exchange is unfolding? What did you notice about the difference between how you responded in the earlier days where you mentioned feeling defensive, and that was the initial response to, what do we get to? What do we try to aim for in a different response, or what’s an ideal way that a situation like that can unfold?

Archer: Yeah. Well, stating, “I’m not racist,” not an effective response.

Chris: Okay.

Archer: Trying to have a conversation with the student one on one is the ideal thing. Finding a way to… really, the ideal thing is to have a better relationship with students that I’m disciplining in the first place, to have a relationship where they feel they can share with me when I’m being overly disciplinarian does help on the front end. Building a better classroom culture helps on the front end of that kind of a situation. Then when it happens, having a one on one conversation to ask. The ideal thing would be, “No, I’m sorry I came off this way. That wasn’t my intent. I didn’t mean to make you feel that I was treating you differently. What can we do to move forward?”

Chris: Yeah. In one of my earlier conversations, we talked about the distinction. A lot of people think of racism or would define a racist is just, if someone does this overt intentional act to hurt someone because of the color of their skin, that that’s what racism is. I think we’ve been learning, some of you all have known this for a very long time, but it’s coming out again in this current conversation, that racism is much more than that. There are systems that we’re part of, things white privilege, that inform who we are, sometimes without us knowing it. Do you think an understanding of systems of oppression or systems of privilege and how they interact, I mean, is that understanding woven at all into the experience that kids in school are having? Are they aware of those things? Or is that something that that we do need to be teaching more? What does that look right now in the classroom setting, as you’ve seen?

Archer: I am mostly in the math classroom, so content doesn’t often flow towards that. In the conflict resolution class, when people have had experiences, there are sometimes topics where we do flow into oppression, and talking about historical oppression, and systems of oppression, specifically against black people, often against immigrants, particularly from Mexico, or other Latin and South American countries. Those are the demographics that typically are the students that want to talk about those, the students in our classroom. I would say, as far as the curriculum goes, I can’t speak to what my fellow teachers are teaching at the high school, but I do think there are some teachers who’ve tried really hard to weed through their history lessons oppression and history of resistance, and how that plays a role on our current situations.

There are definitely teachers who are doing that and I think that is the route to go. I do think there are teachers who, for whatever reason, stick to the traditional curriculum, and don’t focus on that. Maybe their own personal experience, or they just haven’t… maybe their teaching program didn’t emphasize that. It’s definitely an individual thing, and something that the curriculum is open enough to, that teachers can take it in different directions. I would say, I think that curriculum should be very much focused on people understanding. When I look back at my school history, and when I learned about systems of oppression, it wasn’t until college. I think a lot of college students are getting that.

Chris: Interesting, yeah.

Archer: I think that history, especially when it comes to the history of black Americans, the sense that I got from my education was, “Slavery is over, civil rights happen, the black people won, racism is gone, everyone should treat each other equally. There are those people on the far fringes, who are doing these racist things, but that’s not us. That’s not the majority of us,” and that’s a really blinded way of looking at things that doesn’t really address people’s personal experiences, or some of the ways in which our justice department, or other departments, other places still enforce these discriminations against people of color.

Chris: Yeah, and those systems can be really pervasive. They can affect all aspects of life. One of my previous guests, Betsy Schlabach described it, white privilege is this backpack that white people can wear that opens up all sorts of opportunities for them unknowingly, that is not something that may be the case for a person of color, a black person who’s applying for a loan, applying for a job, that kind of thing. Do you think the school system… I mean, I think what I hear you saying is teachers in the school system would benefit from additional training, additional formal curriculum around those kinds of systems and what it means to be in a classroom setting with kids learning about that.

Archer: Yes, I do think there’s a really positive trend in education nationwide, and in Indiana to focus on brain science, neuroscience, and the way that trauma adversely affects the brain and brain development, and how when we’re in these situations of experiencing something that reminds us of our trauma, our brain makes decisions for us to switch into fight or flight mode without us making conscious decisions, and that’s affecting a lot of our behavior in the classroom. I think that there can be a way to connect in the adversity of discrimination, and the trauma experiencing racism and discrimination. That as this trend towards understanding trauma continues, that there’ll be more opportunities and more interest from teachers to take trainings such as implicit bias training.

We’re already taking trainings on de-escalation. There’s been a ton of trainings I took at high school, about how to respond to a person who’s escalating the situation, like ways to hold your body, how to use your tone of voice, and things like that. I think implicit bias training, which I didn’t explain what that means, but is a training where you look at yourself and accept that there might be ways that you’re treating people of color differently without realizing it. It’s not a conscious thing. It’s that racism that’s built into our system where I’m treating somebody differently, and I didn’t even recognize it. How do I step back and notice that and try to change that behavior, based on whatever it is? Some cultural thing that I didn’t realize or that I grew up just reacting towards.

Chris: This is probably an oversimplification, but I’ve even seen some universities that have put some online tools up where you can go through an implicit bias exercise, and it illustrates, in just a couple of minutes, ways that you might see the world, that if you didn’t stop and really think about it, or maybe have it pointed out for you, it’s like I have a bias for or against something or someone, or a type of person. The trainings you’re describing sounds they really get into depth with that, which is really helpful. It does sound something that all of us could benefit from, at some point or another.

I want to transition to the conflict resolution training. We’ve heard, in recent months, really clearly, the calls to defund or significantly reimagine the role of police departments in our lives. People, rightly, I think, noted that this kind of change would require also reimagining how we, as a community, handle and resolve conflict in our life, especially the times where we would typically call the police. The benefit that stands out to me, of course, is that if you don’t have the police showing up to an already tense situation, maybe we remove some of the occasions where black people are subject to police violence.

Chris: I know that that’s a really big topic and a big place to start, but I wonder if you could talk about how traditional models of handling conflict do or don’t work, kind of what you described in the classroom, like just saying, “I’m not a racist,” is not an effective way to handle that conflict, but what does and doesn’t work? What does it look like to do things differently, perhaps in a way that makes us more self-reliant as a community, without having to call the police in every conflict situation that comes up?

Archer: Yeah, so I’d say it’s going to take a lot of work. It’s going to take a lot of personal work and personal desire to react in situations much more effectively, without… so, yeah,

Chris: Yeah, wherever you want to start there, because I know I just threw a lot at you.

Archer: When we talk about traditional ways of dealing with conflict that are negative, escalating the situation towards violence, or even in some cases, ignoring the conflict until it blows up and it seems like there’s irreparable harm, and oftentimes, calling the police. Those, in my mind, they reinforce systems of oppression because I think of oppression as the ability to use your power over somebody else, especially in a historical and a systemic context.

When you’re calling people in to deal with a situation, specifically the police, whether or not they come into it with this intention of being racist or making a racist act, all of this history and all the systems, the way that they’re built, accidentally or purposefully, tend to lead towards these racist actions that end in statistically larger numbers of black people being shot and killed, and larger numbers of black men, specifically, being put in prison for crimes that are similar to what white people are committing. I would say that, if we’re going to dismantle our systems that we currently have, dismantle the police, dismantle the prison systems, it’s going to take so much interpersonal work on our part, we’re going to have to really dissect… I’m going to have to really dissect situations where I’m uncomfortable, versus situations where I am in danger, where I’m physically actually in danger, and be able to differentiate that. I’m going to have resources to reach out to when I’m in physical danger, that are going to help de-escalate that situation without…

Let’s say I’m in a situation of domestic violence, and my husband is attacking me. Who am I calling to help de-escalate that, to get me out of that situation without them condemning that other person to this system that doesn’t exist anymore of imprisonment? What are we doing with people who have committed these crimes? How are we helping them to actually rehabilitate or repent, or whatever it is in this new system? It’s going to take so much more work and effort on the part of individual people.

Chris: You talked about some of the workshops you’ve done, I know, in prison settings and other settings. I mean, what does that look like? Is that kind of personal transformation a one-day workshop? How does it happen? How does it unfold? What have you seen?

Archer: It’s a lifetime process, though there are moments where people transform, or you can transform yourself or a situation that seemed very big, but it’s never a one hour or a one-day thing. This goes back to something I think about in schools, we learn math and English, and Science and social studies. There’s no class on learning to be defensive when someone’s yelling at you and how to respond appropriately. In these workshops, the thing that I’ve taken the most from them is these little tools, this tool belt that you have to build for yourself. How am I going to react and respond, when what I want to do is punch someone?

What am I going to do to preemptively help myself not be in those situations, but not in a way that’s going to ignore conflict? When I’m in that situation, what am I going to use? Am I going to use my breathing, and am I going to walk away? Am I going to have some way of expressing my emotions that helps the other person empathize with me? Am I going to listen, and just let them rant at me and rant at me, and try and respond reflectively to that, and show them that I’ve heard them, so that they can see that I’m in this conversation? There’s this whole bag of things that you can use to try and respond to people when you’re in a situation where emotions are very heightened. Yeah.

Chris: I mean, I hear you describing strategies and tools, but I think I’m also hearing you say that to even get to the point where you could start to pull those tools out of the bag, you have to do a lot of work on yourself first to understand what your responses are, what your biases might be. Is that where you start in those kinds of workshops?

Archer: Yes. And what your triggers are based on your experience. We all have these experiences wrapped back into what I was talking about with trauma and your neuroscience. Your brain is wired to react to situations based on experiences that you’ve had previously. One, I can react and I can be triggered, and then there’s, I can recognize what just triggered me, and then I can watch for that. Becoming conscious of these subconscious processes in our brain is one of the steps to being able to react more positively in these situations.

Chris: Yeah. I mean, I really appreciate the distinction you made of the difference between feeling physically unsafe, and just being uncomfortable. I mean, I feel like that applies broadly to all kinds of conflict, but I mean, so much of the conversation about racism, and especially how white people are thinking about their relationship to people who don’t look like them seems to be about discomfort that in the past, has been pushed back into that system. Now, it’s like, how can we actually confront that? How can we understand the discomfort that we might be feeling, where that’s coming from, what the origins are, and then what to do about it?

I could imagine that, if you do that work, that has a real positive impact in just day-to-day interactions of all kinds, but especially in situations where you find yourself, yeah, around people who are not like you, and especially in racial differences. Do you have success stories…Have you seen transformations happen that give you hope about that kind of… I know you’re saying it’s a life-long process, but about that kind of transformation, that kind of work being effective?

Archer: Great question. I mean, I’ve had transformations in myself, like what I was talking about earlier, with going from wanting to respond to my students saying, “I’m not racist,” to getting to a point where it doesn’t matter because that person felt like I was treating them a certain way. That’s what’s important in the situation. I’d say, I’m trying to think about…

Chris: Or even just what AVP, The Alternative to Violence Project that you mentioned, the goals that they work on as a project. What are some of the highlights there, where those results are seen in our society or in communities?

Archer: I mean, because the project is focused so much around interpersonal change. It is all these stories, and people have these stories, and we often share these stories of personal transformation or personal change. I mean, a lot of these stories do come from prison, so it can be as simple as a person in prison had a positive interaction with a prison guard for the first time ever-

Chris: Wow.

Archer: … because they listened to the prison guard share a story about why they had just reacted so negatively or so aggressively, and they had tried to speak to them calmly. Just little things like that. AVP is definitely about trying to find ways in your own life to change things, to bring about these resolutions by listening, and reflecting, and interacting in ways that are going to open people up to you. It’s very small. It’s not these big moments most of the time. It’s not these big shifts or changes. It’s very interpersonal changes, and so I can think of these times where I’ve been able to hear people better, and been able to explain myself better, and come to a better understanding of something because of that.

Chris: That’s great. We just have another minute or two left, and I’m thinking about, if someone is watching this today and they feel… Someone might be sitting there saying, “I don’t feel like I’m a racist, but I want to be a part of the solution. I want to do some of this work. I want to think about what my biases are, and how that affects my interactions. I want to be better at conflict resolution. Is there a place that you would point them toward to start that work or to continue that work, whether that’s something they can do on their own, or through a program or workshop that you’ve been involved with?

Archer: I think that’s a great question. I think in our community, I mean, we have so many wonderful groups that meet and work together, but I do think it’s often hard. You have to really work to get connected sometimes. Do a lot of research and look out there for a program or a group. Right now, there are so many really awesome webinars and things on… I would really suggest where I got started, just trying to find some webinars, finding other people on the internet talking about these kinds of things, and listening to those and feeling uncomfortable, and really exploring how you feel. Listen to something you really don’t agree with, that you really don’t agree with and then explore why you’re feeling uncomfortable and what it is you that don’t agree with, and then try to just keep pushing that.

Chris: Awesome. Well, that’s a great suggestion and a great place to start. Archer Bunner, thank you so much again for taking the time to talk with me today. I really appreciate the conversation and we’ll keep it going from here.

Chris: I’m here now talking with Bill Engle. Bill, I really appreciate you taking the time to join me on the show and talk a little bit about some topics that I think are really important to the community, so thank you.

Bill Engle: Sure. Thank you, Chris. I appreciate you doing this.

Chris: Bill, you’ve played a lot of different roles in this community, and I wonder if you can briefly tell us about your background here.

Bill: Okay. I came here in 1987 to work at the Palladium-Item. I worked at the Palladium-Item for a little over 25 years as a number of different things, an editor, a sports editor, a features editor, reporter, and at the end of my career, I was doing special investigative projects, and covering city and county government. I raised two daughters here and was involved with them in the sports that they were in, and also other school events and things. Since I’ve retired in 2017, I’ve been involved with a number of organizations, including the Whitewater Valley Pro Bono Commission, the Society for Preservation and Use of Resources.

Bill: I served four years on the Richmond Parks Department Board of Directors, and also on the Plan Commission. I’m still on the Richmond Advisory Plan Commission. This is, I think, my fourth year. Also involved in veterans, and Veterans Affairs. I’m on a committee for the VA called the Veterans Stakeholders Committee that serves as a go between, between veterans and the VA, and we handle issues that they have with not getting services and things like that. Richmond has become my home. There’s just no question. I’ve never lived anywhere as long as I’ve lived here, and I do like the community, and I’m happy to be a part of the community. That’s why I ran for City Council. I guess that’s the other thing I should mention.

Chris: You buried the lead there, yeah.

Bill: Yeah. Thank you. I did run for City Council last year and was elected as the representative from District Three.

Chris: Maybe now it’s just a good time to mention, I always feel it’s important to say as a quick note of full disclosure for the audience, Bill, you and I are friends and I was also a contributor to your campaign for Common Council last year.

Bill: Good to note that.

Chris: You’re a member of Richmond Common Council, and I know that you’re not here to speak for all of Council and you can only speak for yourself. It’s also always good to note Council’s a legislative body. It has limits in the kinds of actions it can take and the oversight that it can exercise, but on these shows, I’ve been having some conversations with folks about this moment in history and the movement that’s happening around thinking about racism, and thinking about discrimination, thinking about the problem of incidents of police violence. There’s just big topics. I wanted to ask you a little bit. Presumably any conversations about police department budgets and that kind of thing would eventually flow through Council. I know that’s got to be on everyone’s minds, but we’re in a time, I think, where people are looking for leadership in lots of different places.

I do wonder, what kind of role you think members of Council, and maybe city government just more broadly, can play in the community as we wrestle with racism, discrimination, diversity and equality on a local level. Yeah, what are your thoughts on that, on what role Council might play?

Bill: Well, it’s a good question. I think it’s an important question right now. Unfortunately, I’m new to Council. I came on 30 days before the pandemic became a thing that’s really interrupted all of our lives, and my life on council. I want to preference anything I say by saying that I’m still learning about being a councilman and my role as a councilman, and working with department heads, and et cetera, et cetera. But I do think this is an important discussion that we have now. It is a discussion that we as council people I’m sure will have, as we meet more regularly that are not the Zoom meetings.

It is also a discussion we need to have with the Mayor to support the mayor in his efforts at both training of police and fire department heads, the ambulance service, and also in recruitment, diversity in recruitment. Those are things that I think I, as a council member, can discuss and make sure that they are a part of our efforts going forward. I did get an email from someone a month ago about defunding the police. I have to say, I’m not really in favor of defunding the police, but I think we need to look at those budgets. If you know how budgets work, the city spends way more than half of its budget on police and fire.

I think we spend $6 million plus a year on both, on each one, and then the next closest is parks at about $2 million. It is something we need to discuss, something that we need to look at. I know there have been complaints about the militarization of the police department. It is worthy of discussion. We have to consider safety for our citizens, but we also have to consider how the police and fire, and every other department head represents the city to our citizens. It is a discussion that we will have.

I can tell you also in about a 32nd discussion at the last council meeting with one of the other council members, we talked about tax abatements and how we hand out tax abatements. One of the criteria is do they pay a living wage? I think that’s something that we need to look at. If we are going to give abatements to companies, maybe we could look at them paying $12 or $13, or $15 an hour to their employees, but those are some of the ways we can look at that.

Chris: Yeah. Well, and I’m glad you mentioned that. I mean, it’s just so important to recognize how so many systems are connected together. The ability of any given person in our community to make a living wage ties directly to the opportunities they have for, say, home ownership or investing back into the community, spending money in the community that ties into the services that we have available. We could probably have a whole separate show, and I may in a future episode-

Bill: Sure.

Chris: … on the question of the role the police department has, and when there are calls for defunding or significantly changing how the police department operates, the immediate conversation that comes up after that is, well, what does that mean for the frontline mental health services that first responders are often involved in, and especially in a small smaller community like Richmond in Wayne County, and the Whitewater Valley? There’s so much to unpack there.

Bill: Sure.

Chris: I mean, I think people generally want to know that a body like Common Council and the city government is taking all of that into consideration, and that people who represent us are able to receive emails, like you mentioned, and hear what people are thinking about, what their requests are, and balanced those with the needs of the community. I know you’re new to Council. Does it feel like there’s some momentum there? Whether it’s talking about racism or some of those other challenges, is council a place where you think good change is possible in those ways?

Bill: I think that it’s possible. I can’t say that we’ve had any in depth discussions. In fact, we were meeting… the democrats on council were meeting as a group with some of the leadership, including the mayor and other people, the head of Amigos and some other organization. Of course, we’ve stopped all that and I really missed that. I hope it’s something that we can resurrect, but I do think we are leaders of the community because we are elected officials who are looking at budgets every day and passing ordinances, so it is something that we can look at.

Bill: I think there are opportunities there for discussion, certainly with the mayor, certainly with the police and fire chiefs, and other people of sanitation. I mean, they’re in the community. They’re also the face of the administration. There are things that we can do to continue this conversation, and I think we need to do that. I know we need to recognize the efforts of our citizens, and to keep this conversation going, but again, I can’t say specifically what we’re going to do at the meeting Monday night or anything.

Chris: Yeah. I mean, you and I have talked about the challenges of, we use the phrase ‘keeping the conversation going’, and we’ve acknowledged together that spring 2020 is not the first time that our community has had opportunities to confront racism, to think about racial discrimination. There have been organizations, there have been community projects. There have even been reporting that you tackled is as a reporter to help us think about what’s happening in our community, where is race and racism playing a role, and sometimes those can create momentum, but it’s pretty rare to see something that’s actually sustained.

I think that’s a real concern for me. I think it’s a real concern for a lot of people who want it to be more than a conversation, who want it to turn into action. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about some of the projects you were involved with maybe as a reporter, where you maybe put something out into the world and what you noticed about how people responded to that?

Bill: Sure. I think it was 2004, I did a series on race and race relations in the community. I think it was a four-week thing, every Sunday for four weeks. It escapes me now, but we looked at race relations, race and education, race in the economy, and I think race in government. I don’t remember the fourth one, but one of the things that struck me when I was reporting on education was, I did a study of African American students, and I think they were male students who entered Richmond High School. Then four years later, I looked at how many of them graduated. I think the number was 27%, which-I was astounded, and I really thought when I reported on that, that that would really hit a chord in the community and spark some conversation. There was some. There were support. There were a couple of business leaders that made note of that and said they were interested in maybe even contributing some type of effort, but I didn’t get the response that I expected, especially from school officials, including the school board. I didn’t actually hear any response at all. Even if people were going to refute it or criticize it, that would have been okay, but just the fact that there wasn’t a lot of discussion was… I was surprised. I was very surprised at that.

There was a discussion, we ended the series with an organizational meeting at the Townsend Center at the time, and we had black leaders and also members of the school board, city council were there, and I think the Mayor was there, I don’t remember. But it led to a reunion at Townsend Center, which also led to a series that I did called 50 Weeks of Success where I looked at our citizens and the roles that they… where they came from, how they overcame obstacles to become successful. That was very gratifying, and I think it was well received.

Not initially, because I think people thought that I was going to do 50 weeks of African American people in the community, but that was never the intent, and I explained that to a number of people, but I think it was very successful in celebrating some of the successes. There was one woman that got her GED after six years of trying, and I went to her graduation. When they gave her, her diploma, they had put it in a case, and she just hugged it and started crying. That was terrific. I mean, that was just a wonderful thing. For me, it was enlightening, and I think there were some positive things, but I didn’t get the response that I was hoping for.

Chris: One thing that really strikes me as you’re talking, in some of the other conversations I’ve had for the show, it’s become clear, if it wasn’t already, that part of working on racism is embracing discomfort in a way, and it’s embracing maybe discomfort because of truths that we learn about ourselves, about our own backgrounds or biases, or the way that we’ve come to see the world, and figuring out how to challenge that. I think that also needs to play out in the community, organizations, leadership, people in positions of power, especially white people, to be willing to say, “I’m going to challenge myself to think about how I look at the world, how I look at people of color, minorities, black people, and what my relationships there are.”

I contrast that with your time as a reporter. If it’s fair to say, you were going after the truth of the matter. You’re going after the facts of the matter, trying to report, and often that meant going toward the uncomfortable, I can imagine, even in the study that you mentioned, that you did of high school graduation rates. When you take something that’s uncomfortable like that, and you put it out for public consideration, as a community, I think we really struggle with that. There’s often a strong impulse to say, “Yeah, maybe that’s a problem, but here’s all the good things.” Those good things may be real, and they may be true and worth celebrating, but that doesn’t do anything to help the challenges or the discomfort that we put out there. Did you find ways…

I mean, as someone who’s lived here for a long time, and you are proud of the community, you seem to celebrate what Richmond is, but then you were also involved in poking and prodding at some of our challenges. How did you balance that as a reporter and as a community member? How do you do that now as someone working for the benefit of the community, but also trying to call out some of the things we need to work on?

Bill: It’s a great question. I did get some blow back on some of the series. I did a series on homelessness, and I actually spent 24 hours homeless in the city. I know that that’s not a good probably representation, but I always looked at my work as being maybe I’m going too far, but I always believed it was a service to the community. When I did get criticism, and I did get criticism, I get people that called me and stopped me, and asked me why I was doing what I was doing.

I would always say, “I’m just trying to reflect your community back to you. Whether you agree or disagree, I’m still looking at who lives here, how they live, what are the issues that we face?” It’s not a question of we always find nice pleasant stories about people doing wonderful things, but we also know that there are other issues where people are living in difficult situations, they don’t have the opportunities and maybe never have had the opportunities that some of our other citizens have had. I always felt that it was important to find out, to interview people. I mean, I’m a white guy and I don’t have a lot of black friends or Latino friends in this community.

As I see it now, it is an opportunity to educate myself and to communicate with people to figure out what the issues are here. I see that as my role going forward as a councilman, and as representing my community, but again, I looked at it as, it was the truth as I could find it and reported fairly and honestly, and I always thought those were important things to consider in your community. The only way that we are going to be a better community is by facing those things and facing those realizations, that we do have work to do and we need to continually work on making ourselves a better community.

Chris: Yeah, and I think there’s this concept of everyone coming together and helping Richmond and Wayne County, and the area celebrate our strengths, and show ourselves as a strong community. I think about that as an important effort, but I also recognize and I think that’s part of what you’re saying, is that if we don’t also stop to look at the challenges along the way, and we just try to sweep those under the rug, they’re going to come back and bite us. For one, because we’re not actually being honest with ourselves about how we’re doing as a community, and then also just purely as a matter of being good people to each other.

If we are leaving behind significant parts of our community in terms of residents or the kinds of experiences people have here, if we’re not acknowledging their stories or not thinking through what their experience of the community is, then we can’t ever really get to a place where we have a unified community. It’s just some part of the community might be coming together. I think about that when it comes to the work of council, and also as your work as a reporter, just thinking about that long term arc of figuring out what’s going to work for everyone in the long run.

You and I both attended a recent march that went through Richmond, and it was a moment where I felt proud of the community because a large chunk of people from lots of different backgrounds were coming together to acknowledge a hard thing, to celebrate some good things, and to try to move something forward. I wonder if you could say a little bit about what that was like for you to show up for that march, be a part of it knowing you were there in multiple roles, multiple hats on. What was that like?

Bill: Sure. It was a really good experience, I have to say, and I agree with you, I was proud of our community and proud of the response that I saw. I was especially excited that there were a lot of young people there, because if you know city and county government, I think you’ve written about this before, it’s a lot of older people, that we hope we are in touch with the younger generations. I don’t know that we ever are. I’m not a young guy, and I think I was excited by the activism that I saw. I was a little disappointed that I didn’t know a lot of the people, especially the black people. As a reporter, you get to know a lot of people because you go to a lot of events. You cover a lot of government events and other events throughout the community, and you get to know a lot of people, and some of their kids and things like that, grandkids, but I saw a lot of people I didn’t know, which, it was okay.

I mean, it’s still exciting, but it was a little troubling. I hope there’s a way to meet some of these people and to listen to them. I think that’s the one thing that I took from the demonstration was, you have to listen to people and you have to understand their perspective, and that’s going to be important. I was a little disappointed that there weren’t more people from Council and other representative boards there, but again, that’s up to them. I felt good about my role in that. I was pleased that I did it. I was inspired. As you know, the woman that organized the thing was, I think, a high school student, and that’s exciting to me. We need young people to be involved, just like we need old people and middle aged people, and black and white, and Latino and Asian and et cetera, et cetera. I hope we can keep that going and move that forward.

Chris: Yeah, and I think about maybe five years ago, a demonstration going through the streets of Richmond, I think, would have been seen in a much more negative light, just culturally, because of the way that our city works. I think marches, demonstrations, protests have traditionally not been seen as an okay way to express oneself. I remember when the Occupy Wall Street movement was happening, there were a couple of folks who took it upon themselves to stand downtown with some signs related to the concerns of wealth inequality in our country. They were yelled at and not treated very well. I understand that for a lot of people, acts of disruption can be seen as threatening or can be seen as uncomfortable-

Bill: Sure.

Chris: … but what I saw in participating in it was that, if we have taken a lot of what might have happened in the public square, if we’ve taken that online and people are in their factions on social media, and holed up with other people who think the same way, then we don’t have as many opportunities to express ourselves. That march and marches like it are a place where people can have a voice, they can say, “Hey, this is a point of view you might not be aware of or exposed to,” and I think it’s really important. I mean, I’m really glad that you participated in that.

I’m really glad that other folks who, yeah, may not have even agreed with everything that was on every sign, or everything that was said there. Do you have a sense of… like, when Richmond has made progress on hard issues, racism or other issues in the past, what have been the kinds of things that have led to that progress? Is it conversation? Is it committees? Is it government leadership? Is it something else entirely? Do you have a sense of that? I know that’s a big question.

Bill: Yeah, it’s a big question, and I bring the sense of my years as a reporter more so than my years as a councilman, because I haven’t been a councilman very long, but I think confrontation is part of it, and that you hope leads to conversation. I can remember when the city council, and I can’t remember the year but was considering its affirmative action and updating its affirmative action ordinance. There was a request that we include gay, lesbian people in the protection.

Chris: Right, making sexual orientation a protected class.

Bill: Yes. There was a major response from conservative folks, including ministers about that, that it was a horrible thing, and actually it wasn’t included, but we needed to have that. We needed to have that confrontation and that led to discussion. These things have to progress. I always think that’s how they progress, is we have to make them progress. As you know, there’s no progress just on its own in general.

You need to have those issues raised and discussed, and then you hope that facts will take over, that there will be progress, because I always think there’s a lot of citizens that are in the middle and they’re okay with it. They’re not opposed. They don’t hate Black Lives Matter, science and that kind of thing, but they need to be aware of these situations, whether it’s across the country, in our state or in our community. That’s how I think you have these things, is to have a thorough discussions about them and confronting the issues.

Chris: I’ve always appreciated, I mean, you’ve talked about times where you’ve confronted someone in your role as a reporter and say, “Hey, I’m writing a story. I need to ask you some questions that might be a little uncomfortable,” but then you can have that conversation, you can have that confrontation, and then you can go back to being members of a community that are all trying to do the right thing, or move things forward. It doesn’t mean burning bridges and tearing everything down. I think that’s helpful for people to see models of, yeah, we can have hard conversations, and then we can move forward. In just the little bit of time we have left, what do you hope is next for this conversation about racism and discrimination in our community? What do you think our best next steps might be? Or what do you hope to be a part of in that?

Bill: I hope to be a part of the group. I know there is a group that’s organizing to continue the conversation. I think Reverend Ron Chappell is part of that organization. I hope to be part of that and to contribute in any way I can, but again, on Council, I hope we can have a conversation, and I hope we can have a conversation with the Mayor about his practices for recruitment, and his diversity practices. Also, then I again, I need to educate myself. I’m not connected to the black community, I’m not connected to the Latino or Asian community, and I need to have some type of connection. I need to take the time, whether it’s to go to a community festival, to go to a march, to go to these meetings. Excuse me. The last thing you want to do is have a bunch of meetings and then you’re done, because we’re not done it.

I guess what I’d like to see is this thing continue. I think it’s important. I think we need to include as many people as possible from throughout the community. I think that’s how you see things change. Again, I thought of the demonstration as a way to confront this, and we need to confront it and then talk about it. You mentioned my years as a reporter. I had screaming matches with the Mayor and with members of council, and county. Ken Paust and I yelled at each other a couple of times, but I have the utmost respect for him. I think he respects me. We’ve always been able to work through these things. That’s how you work through these things. You do them.

Chris: Well, Bill Engle, thank you so much for joining me. Thanks for your time and your insights, and the work you’re doing, and best wishes.

Bill: Thank you, Chris. Appreciate it. You take care.

Chris: You too.

Leave a Reply